Sharon Lavigne was teaching a special-education class when her daughter called to tell her about the Sunshine Project. Named for its proximity to Louisiana’s Sunshine Bridge, the operation, helmed by the Taiwanese behemoth Formosa Plastics, was on track to build one of the world’s largest plastic plants. Already the air Lavigne breathed in her native St. James Parish was some of the most toxic in the United States. Now Formosa planned to spend $9.4 billion on facilities that would make polymer and ethylene glycol, polyethylene, and polypropylene—ingredients found in antifreeze, drainage pipes, and a variety of single-use plastics—just two miles down the road from her family home. The concentration of carcinogens in the atmosphere could triple.

“It hurt me like an arrow through my body,” Lavigne told me when I visited her at her home in Welcome, Louisiana, last December. “Everyone else was saying we had to move.” Within a few months of learning about the Sunshine Project in spring 2018, Lavigne, who’s 69, organized a community meeting in her den. “Ain’t gonna happen,” Lavigne said. “We not gonna be moved out and bought out and throwed out the window.” The group went on to found Rise St. James, a faith-based nonprofit with the mission of halting industrial development in the parish. “I was not a person who would speak up,” Lavigne said. “Boy, did that change.” That fall, Lavigne was spending so much time organizing marches and speaking publicly about Formosa that, after 39 years of teaching, she retired. Then two of Rise’s members died—one of cancer, the other of respiratory distress and other medical problems, conditions Lavigne links to pollution from existing plants. Stopping Formosa became her full-time job.

In Louisiana—where more than a 12th of the country’s estimated 4 million enslaved people lived prior to the Civil War—descendants have the right to visit their ancestors’ graveyards. So when Lavigne learned in late 2019 that enslaved people from the Buena Vista Plantation, whom she believes she’s descended from, may have been buried on Formosa’s proposed building site, she tried to visit. Upon arriving, she said authorities told her she was trespassing and that if she returned, she’d be arrested.

Back in July 2018, Coastal Environments, or CEI, an independent archaeological and environmental contractor, had alerted the Louisiana Division of Archaeology about two possible cemeteries on Formosa’s land, based on historic maps of the Buena Vista and Acadia Plantations. Formosa’s archaeological consultants had missed those sites in their initial survey, but after being instructed by the state to look again, they found and fenced off the Buena Vista cemetery. According to the Center for Constitutional Rights, a legal-advocacy nonprofit, Formosa made no public announcement of this discovery. Lavigne found out about its existence more than a year later via a public-records request submitted by Rise’s lawyers. The Acadia cemetery, Formosa reported, had still not been located and may have been destroyed by a previous owner, but both CEI and the Center for Constitutional Rights dispute that claim, arguing that Formosa’s surveyors searched in the wrong area. In March 2020, CEI identified five additional anomalies on Formosa’s territory that could also be slave cemeteries and have not yet been excavated. (“Archaeologists conducted thousands of shovel tests … no remains have been found other than at the Buena Vista site,” Janile Parks, Formosa’s director of community and government relations, wrote me via email. “When [Formosa] learned of remains at the Buena Vista site ... the company immediately coordinated with the appropriate authorities. [Formosa’s] archaeological investigations of the site have been transparent and are matters of public record.”)

Rise formally requested access to the Buena Vista cemetery last year for Juneteenth, a holiday commemorating the day that enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, found out they were free—more than two years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. Formosa denied the Juneteenth request, and Lavigne took them to court. In a statement to the Associated Press, the company’s lawyers questioned the need for the ceremony on the basis that archaeologists couldn’t confirm the ethnicity of the human remains. District Judge Emile St. Pierre sided with Rise, giving the group temporary access to the property. “We need healing,” St. Pierre said at the end of the hearing. “Let’s look at where we are in America.”

The conflict between Rise St. James and Formosa comes at a time when many Americans are insisting the country acknowledge and address the horrors of slavery and its repercussions. Around the country, cities have debated whether to take down Confederate monuments, inciting protests. Down the river from St. James Parish, in New Orleans, several monuments have already been removed, and the city council is preparing to rename schools and streets that honor Confederate officials and segregationists. Yet what’s happening with the Buena Vista grave site is unique. Unlike monuments, which are symbolic, the cemetery contains human remains, which have endowed the land with enough cultural capital to sway a judge, at least temporarily, in favor of the community that claims it. Like a time capsule, the graves link the petrochemical industry to the plantation economy, revealing how Louisiana’s petroleum industry profits from exploiting historic inequalities and showing how one brutal system gave way to another.

Two hundred years ago, nearly every inch of Mississippi River–adjacent land south of Natchez was part of a plantation. Rich soil made for strong harvests, and river access allowed for the easy export of goods. In Louisiana, those plantations grew sugarcane, the “white gold” that propelled the southern economy. Arduous to harvest, grueling to press, and treacherous to boil, sugar had been a rare commodity, a crop barely worth the effort, until the transatlantic slave trade solved the problem of labor. In the half century preceding the Civil War, 1 million people were sold into the Deep South, relocated from Virginia, Maryland, and Kentucky to Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Along the lower Mississippi River, the population of enslaved people quadrupled despite their being worked so hard that death rates often exceeded birth rates. Nonconsensual laborers produced a quarter of the world’s cane sugar, which became so lucrative as a crop that, for a time, the nation’s highest concentration of millionaires lived between Baton Rouge and New Orleans. Back then, Louisiana was the second-richest state per capita, a staggering feat when you consider that almost half of its residents lacked legal ownership of their bodies.

Drive along the lower Mississippi River today in southern Louisiana, and you’ll see vestiges of that history, though the state now has the second-highest poverty rate in the union. Houses are small and trailers abundant, but more than a dozen plantations still exist, offering tours, meals, wedding venues, and overnight stays, their advertising thick with honeyed narratives about an opulent white lifestyle long gone. Until two years ago, a sign at Rosedown, the most visited plantation in the state, described enslaved people as “happy” with a “natural musical instinct.” Ormond Plantation’s website laments the hard times suffered after “the war between the states.” Only one plantation museum in Louisiana, the Whitney, focuses exclusively on the labor and culture of African and African-descended people. There, visitors can pay their respects at memorials for the enslaved, tour slave cabins, and peek in the overseer’s shed, where the tools of chattel—neck braces, balls and chains, leg irons, and paddles—hang from the walls and ceiling.

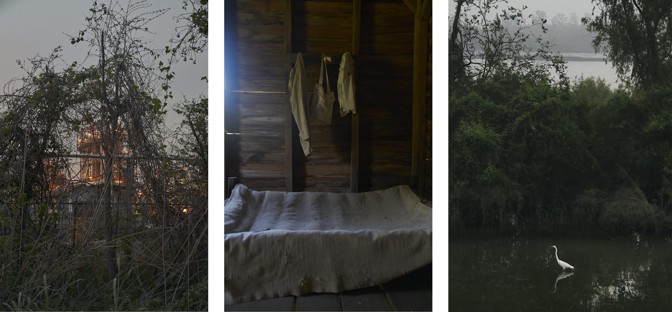

The land adjacent to the Mississippi River bears the marks of another brutality, unmissable from a car, barge, or plane. Beside the restored plantation houses and acres of sugarcane that still stripe the landscape, a newer economy chugs and chuffs. More than 150 petrochemical plants operate along the 85-mile stretch of land from New Orleans to Baton Rouge. Stadium-size holding tanks, miles-long pipes, and flaring smokestacks create skylines reminiscent of cities, though, aside from the occasional security truck, few humans are visible. Names such as Syngas and American Styrenics make it difficult to tell what each plant makes, but whatever it is, you can smell it, cough it out, and sometimes see it falling, a soft yellow rain from a discolored sky. The sheer quantity of plastics, synthetic rubbers, electronic components, and fertilizers manufactured here is enough that experts call the area “the Silicon Valley of the petrochemical industry.”

The Sunshine Project has an unmistakable doomsday quality. According to a 2020 Pew Research Center poll, about two-thirds of Americans believe the federal government should do more to reduce global climate change, yet Louisiana’s Department of Environmental Quality has written permits for the proposed facilities to emit more than 13 million tons of greenhouse gases a year, the equivalent of three and a half coal plants. In addition, extensive research on the damaging effects of plastics has spawned a global movement to ban single-use items such as bags, straws, and cups. Despite this, Louisiana’s governor, John Bel Edwards, defends the Sunshine Project, hailing its proposed facilities as an economic win. In addition to tax revenue, Formosa anticipates that it’ll support an estimated 8,000 temporary ancillary positions in the construction and service industries and create 1,200 on-site jobs with an average yearly salary of $84,500, almost triple the median household income for St. James Parish’s Fifth District, where the plants would be located.

Lavigne thinks those numbers are spin. The state has often equated industry with progress, but petrochemical facilities have a documented history of outsourcing labor. Lavigne is doubtful that Formosa will hire people from her community, besides for low-paying security work—a perspective her parish councilman, Clyde Cooper, shares. “These new companies don't hire anyone from the community,” Cooper told me over the phone. “People come, even from outside of the state, to work in construction and in the plants.” (In 2018, Cooper voted to back the Sunshine Project, on the condition that the company agree to preferential hiring from within the parish, plus funding for a hurricane evacuation route and free cancer screenings for residents of the Fifth District.)

As for taxes, Louisiana’s notoriety for corporate welfare has long made it a haven for refineries and manufacturers. Since the 1930s, the Industrial Tax Exemption Program has allowed a state-level board to make decisions about parish-level property-tax exemption. According to a study by Together Louisiana, a statewide network of community organizers, from 1997 to 2016 the ITEP board approved all but eight of 16,931 corporate-tax-exemption applications. In 2017 alone, those exemptions cost state parishes about $1.9 billion, money that could’ve been spent on local parks, libraries, and schools. In 2016, Edwards issued an executive order returning decision-making power on property-tax exemptions to the parishes, but he backtracked in 2020 when he gave corporations the option of appealing local decisions to a state board.

And yet, taxes and jobs are the least of Lavigne’s worries. What keeps her up at night are emissions. In the entire U.S., only one plant emits chloroprene, an ingredient in wet suits and Koozies that’s linked to liver and lung cancers. That it’s in southeast Louisiana is no accident. As reported by ProPublica, the state has a reputation for having policy makers sympathetic to industry, and lax environmental regulation. Since the 1980s, residents have been documenting high rates of miscarriages and cancer, earning the parishes along the Mississippi River the nickname “Cancer Alley.” “Ask anyone,” Harry Joseph, the local pastor of the 114-year-old Mount Triumph Baptist Church, said during a bike tour highlighting environmental injustice. “There’s not a household here that hasn’t dealt with cancer.” The region has improved considerably since the 1963 Clean Air Act and the 1972 Clean Water Act created federal pollution limits. But in the past decade, hydro-fracturing—the practice of injecting pressurized liquids into bedrock in order to extract fossil fuels—has produced a glut of natural gas that’s fueled the establishment of new chemical plants, and environmental progress is expected to backslide.

Already under scrutiny for allegedly protecting the industry it’s meant to regulate, Louisiana’s Department of Environmental Quality has proposed an air-emissions allowance for the Sunshine Project that includes: 7.7 tons of ethylene oxide—a carcinogen linked to breast cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, leukemia, and miscarriages; 36.58 tons of the carcinogen benzene; and 1,243 tons of nitrogen oxides, which cause and exacerbate respiratory illnesses. (Formosa “has relied on sound science in design of the Sunshine Project and is confident it meets all regulatory criteria,” Parks said in her email. “Protecting health, safety and the environment is a priority in project engineering, design and operations.”) In a still-unresolved 2020 lawsuit, a coalition of environmental organizations allege that these quantities surpass federal air standards and that the Louisiana DEQ failed to consider existing air pollution and disproportionate racial impacts in its assessment. (“Our permits were issued in accordance with all applicable state and federal laws,” Gregory Langley, the press secretary for the Louisiana DEQ, told me by email. “Great care is taken in the site selection process to identify a safe location for the plant that is protective of the adjacent communities and their residents.”)

At the heart of the dispute is the Louisiana Tumor Registry, a project from Louisiana State University’s School of Public Health meant to track cancer risk throughout the state. Although the registry reports no elevated cancer risk in St. James Parish, critics point out that its data neither take into account residents’ proximity to plants nor measure the impact of new facilities. This missing information matters. The 824 residents of Welcome aren’t the only ones in the immediate vicinity of the Sunshine Project. Fifth Ward Elementary is a mile away—nearly all of its 123 students are Black.

It’s not by chance that 158 years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, rural Black communities bear the environmental consequences of Louisiana’s biggest industry. Overlay a map of southern Louisiana’s petrochemical and petroleum plants with archival maps of the area’s plantations, and you’ll find that in many cases the property lines match up. “One oppressive economy begets another,” Barbara L. Allen, a professor of science, technology, and society at Virginia Tech and the author of Uneasy Alchemy, a book on environmental justice in the region, told me over the phone. “The Great River Road was built on the bodies of enslaved Black people. The chemical corridor is responsible for the body burden of their descendants.”

Allen’s research examines the extractive economy: how sugar monocropping transitioned to petrochemical manufacturing. During Reconstruction, the Freedmen’s Bureau gave land grants to Black maroons and the formerly enslaved along the lower Mississippi, parceling out slivers of large plantations to extended-family groups as part of reparations, while returning the bulk of the land to white owners. The result, Allen wrote in a 2006 article, was “a pattern of large, contiguous blocks of open land under single ownership … separated by communities of freed blacks and poorer whites.” Like plantations, petrochemical and petroleum plants benefit from large acreage and easy access to some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. When the oil industry moved in during the first half of the 20th century, corporations began buying up the intact plantations. More than a century later, the pattern established during Reconstruction is still visible, only instead of plantations, Louisiana’s historic free towns share fence lines with plants.

The proliferation of petrochemical plants along the lower Mississippi is undoubtedly slavery’s legacy. Before the Civil War, the state relied on the plantation economy. Today it relies on an industrial economy, which continues to disenfranchise residents. In her 2016 book, Strangers in Their Own Land, the sociologist Arlie Hochschild observes that many rural white Louisianans believe they must sacrifice environmental regulation in order to have jobs. For many rural Black Louisianans, that sacrifice is much starker. When industry moves in, descendants of the formerly enslaved get neither environmental security nor well-paying jobs. Like the plantations and land owners who came before them, petrochemical plants and their leadership have emerged as a new kind of “boss,” determining what happens not only to the land but also to the people who live there. The court case about Juneteenth access to the Buena Vista cemetery illustrates just how much this is a struggle about ownership of bodies: who decides which bodies go where, who has access to the bodies of the deceased, and ultimately who determines which chemicals Black people are exposed to.

Politics in Louisiana often revolves around industry. “St. James Parish, on its face, is hunky-dory: fifty-fifty Black and white,” Anne Rolfes, the founder and director of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, a nonprofit that partners with fence-line communities to advocate for environmental rights, said during the aforementioned bike tour. “However, the African American population is mostly at one end of the parish, in the Fourth and Fifth Districts. And where do you think the land-use plans put all the petrochemical plants?” Lavigne lives in the Fifth District, where nine plants are in operation, two are under construction, and four more, including Formosa’s megaplex—which itself includes 14 unique facilities—are proposed. This concentration of industry is enabled by zoning laws. Typically, land-use plans separate residential areas from industrial ones, but in 2014, the St. James Parish council voted to change river-adjacent sections of the Fourth and Fifth districts from “residential” to “residential/future industrial.” “The council will fight to keep the petrochemical plants out of the white districts, but they roll out the red carpet … when it comes to the Fourth and Fifth” Districts, Rolfes said. “It’s worse than redlining. It’s shocking, really. The council has a written plan to wipe out Black communities.” Councilman Cooper acknowledged “biased consideration” in the council’s zoning, but stopped short of calling it environmental racism. “I don’t think it’s strictly on being racist. They got big plots of unused cane and farmland on the river and there’s a rail there and easier access because it’s not as populated.”

Rolfe’s assessment, however, is backed by the local historical record. In 1987, traces of vinyl chloride were discovered in the blood of children from nearby Reveilletown, a historic free town founded in the 1870s. Following a settlement, Georgia Gulf Corp., the owner of a neighboring plant, bought out the rest of that town for $3 million. Two years later, vinyl chloride had contaminated the groundwater in the historic free town of Morrisonville, and Dow Chemical Company spent $7 million buying out residents. In 2002, yet another free town, Diamond, sandwiched between two Shell Chemicals plants, was bought out decades after two fatal chemical explosions. In each case, Black families had little choice but to leave, giving up not only their houses, which pollution had rendered unsellable, but also their community. This repetition of buyouts has created what environmentalists believe is a dangerous precedent: Instead of remedying safety and environmental concerns, plants that pollute can pay their way out of trouble.

Even before the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, the river parishes’ nickname had begun shifting from “Cancer Alley” to “Death Alley.” The kinds of preexisting conditions that make COVID-19 especially deadly thrive here, giving one rallying cry against systemic racism—“I can’t breathe”—haunting significance. Still, the environmental-justice movement, which combines a demand for racial equality with the push for environmental protection, has gained traction in St. James Parish during the pandemic. Shortly before Rise’s Juneteenth ceremony, Formosa announced that it would halt construction on the Sunshine Project until COVID-19 rates dropped in the area. The decision coincided with an increase in negative media attention about its handling of the rediscovered grave sites and an impending environmental lawsuit, which was thrown out when the Army Corps of Engineers announced that it was reevaluating Formosa’s wetlands permits. Though the company resumed “preconstruction” activities such as road building and soil testing in October, Formosa said it would defer major construction until a COVID-19 vaccine was widely available. Work on the property is still halted today. (“The significant economic impact of COVID-19 has contributed to difficulty in evaluating construction,” Formosa’s Parks wrote. “Ongoing legal proceedings also contribute to the delay.”) Meanwhile pressure is mounting to shut down the whole project.

Two U.S. representatives, the Democrats Raúl M. Grijalva of Arizona and A. Donald McEachin of Virginia, are pressuring the Biden administration to permanently revoke the Sunshine Project’s permits. (The congressman who had represented St. James Parish, Cedric Richmond, left his post in January to join President Joe Biden’s cabinet. So far he’s made no comment for or against Formosa.) Experts appointed by the UN’s Human Rights Council have weighed in too, calling on “the United States and St. James Parish to recognize and pay reparations for the centuries of harm to Afro-descendants rooted in slavery and colonialism.” Such support is hard-earned, but how much it will matter in the long run is unclear. “Industry [in Louisiana] has just exploded,” Allen, the Virginia Tech professor, said. “In five or 10 years … I wonder if the region will even be livable.”

Oppression runs deep in southern Louisiana, but so does resistance. On January 8, 1811, a group of enslaved people marched from Woodlawn Plantation in St. John the Baptist Parish toward New Orleans. With each plantation they passed, more people joined, armed with cane knives, hoes, clubs, and guns, until more than 500 people flowed downriver, bent on founding a new Black nation. Within days, the rebellion was quashed. Dozens of Black men and women were killed by federal troops and plantation militia, and many more were sentenced to death, their severed heads mounted on spikes and displayed along a 60-mile stretch of river.

For a time, knowledge of the revolt was lost, a victim of historical amnesia. Over the past decade, though, tours, book publications, and museum exhibits have restored the event to the popular imagination. In 2019, that history came alive when the artist Dread Scott led hundreds of mostly Black volunteers in period costume on a 24-mile march past plantations and petrochemical plants, ending the reenactment at a destination the original insurgence never reached: New Orleans’s Congo Square. “Their rebellion is a profound ‘what if?’ story,” reads Scott’s website. “It had a small but real chance of succeeding.”

In some ways, Lavigne’s work with Rise isn’t so different. When she and her peers organize, the odds are against them. They’re a small group advocating for change in a region shaped by plantations, in a state where politicians consistently choose industry over environment, against a corporation they believe is determined to make plastics no matter the human cost. “We are here to acknowledge the evil of slavery and its aftermath,” Lavigne announced to her online audience and to the few dozen people gathered in person at Buena Vista cemetery last Juneteenth. She placed a bouquet of roses near eight rediscovered grave shafts. “Those were their very bodies. Their very labor,” one onlooker observed. “We honor our ancestors by thriving.” The crowd swayed, singing, “I said, Lord, help me please / I got up singing—shouting!—victory.”

The stories Louisianans tell about their history matter. The 1811 revolt ended in horrific violence, but today that history is often recounted with a kind of instructional reverence. Here were enslaved people who dreamed and organized and marched so that their children might experience a better life. Here were people who were beaten down and rose up anyway, knowing very well that their greatest hope for survival might end with the loss of their life. They strove— yes, they did—and look at how they nearly succeeded.